I get a lot of questions about panning, especially about hard panning and the resultant “Big Mono,” so I thought I’d provide an excerpt from The Mixing Engineer’s Handbook to address them. This applies only to the stereo soundfield as most musicians haven’t entered the immersive world yet.

“One of the most overlooked or taken for granted elements in mixing is panorama, or the act of placing a sound element in the soundfield. To understand panorama (or panning as most of us call it) we must first understand that the stereo sound system (which is two separate audio channels, each with its own speaker) represents sound spatially. Panning lets us select where in that space we place the sound.

In fact, panning does more than just that. Panning can create excitement by adding movement to the track and adding clarity to an instrument by moving it out of the way of other sounds that may be clashing with it. Proper panning of a track can also make a recording sound bigger, wider, or deeper, sometimes all at the same time.

What is the best way to pan a mix element in stereo? Are there any rules? Just like so many other things in mixing, there’s a method to follow that has some good reasoning behind it, although it may sometimes seem that panning decisions can be pretty arbitrary. That said, there are three major panoramic areas in a mix that an engineer must be concerned with: the extreme hard left, the extreme hard right, and the center.

It Goes Back To Vinyl Records

The center is obvious in that the most prominent music element (like the lead vocal) is usually panned there, but so is the kick drum, bass guitar, and even the snare drum. Although putting the bass and kick up the middle makes for a musically coherent and generally accepted technique, its origins actually come from the era of vinyl records.

With the first stereo recordings in the mid-’60s, sometimes the music from the band was panned to one channel while the vocals were panned to the opposite side. This was because stereo was so new that the recording and mixing techniques for the format hadn’t been refined yet, so what we now know as pan pots weren’t available on mixing consoles. Instead, a three-way switch was used to assign the track to the left output, the right output, or both (the center). Sometimes the channels were even dedicated to either left or right, like on the famous REDD console at Abbey Road Studios that was used to record The Beatles and other major acts of the day.

Because music elements tended to be hard panned to one side, this caused some major disc-cutting problems in that if any low-frequency boost was added to the music on just that one side, the imbalance in low-frequency energy would cause the cutting stylus to cut right through the groove wall when the master lacquer disc (the master record) was cut. The only way around this was to either decrease the amount of low-frequency energy from the music to balance the sides or pan the bass and kick and any other instrument with a lot of low-frequency information to the center. In fact, a special equalizer called an Elliptical EQ was used during disc cutting specifically to move all the low-frequency energy from both sides to the center to prevent any cutting problems.

Big Mono

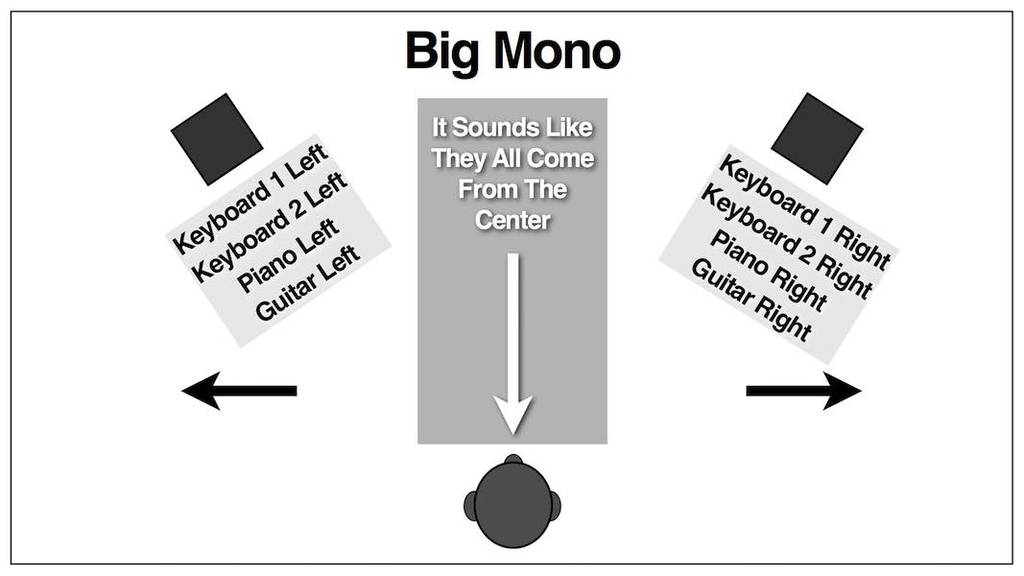

Likewise, as a result of the vast array of stereo and pseudo-stereo sources and effects that came on the market over the years, mixers began to pan these sources hard left and right almost without even thinking, since a mixer’s main task is to make things sound bigger and wider. Suddenly things sounded huge! The problem came later, when almost all keyboards and effects devices came with stereo outputs (many are actually pseudo-stereo with one side just chorused a little sharp and then flat against the dry signal). Now the temptation was to pan all of these “stereo” sources hard left and right on top of one another. The result was “Big Mono,” a phrase coined by the legendary Nashville mixer Ed Seay (see the figure above).

Big Mono occurs when you have a few stereo tracks that are all panned hard right and hard left. In this case, you’re not creating much of a panorama because everything is placed hard left and right, and you’re robbing the track of definition and depth because all of these tracks are panned on top of one another.

The solution to Big Mono is to not pan anything to the hard left or right unless there’s a good reason, then don’t pan mix elements on top of one another. Instead of panning the two channels hard left and right, find a place somewhere inside those extremes (we’ll specifically discuss this in an upcoming section.)

Another solution is to throw away the effected side of the stereo track (keep the dry channel) if it wasn’t truly recorded in stereo and make your own custom stereo patch with either a pitch shifter or a delay.

TIP: Panning narrowly on the same side (like 1:30 and 3:00) provides the width and depth of stereo while still having precise localization within the stereo soundfield.

You can read more from The Mixing Engineer’s Handbook and my other books on the excerpt section of bobbyowsinski.com.