When we look back at its roots, trip-hop was born out of a combination of originality, influence, and adventurous experimentation. In fact, most of the artists that we now associate with trip-hop never sought to make platinum-selling albums, or to even fall into a musical category for that matter.

Bristol Origins

Deep in the 80s, with equal parts New York hip-hop influence and punk-rock DIY ethos, soundsystem DJ culture began to thrive in the southwest of England, with prominent groups like Bristol’s The Wild Bunch coming to the forefront. Besides turntablism, breakdancing, graffiti, and rap, there were strong Jamaican influences that would shape the sounds to come.

What may have begun as a satellite hip-hop movement quickly developed its own identity. Figures such as Neneh Cherry, Nellee Hooper, and Mark Stewart going on to become pioneers of the Bristol music scene in their own right.

The Wild Bunch dissolved into legend by the end of the 80s. But its core members, Robert Del Naja, Grant Marshall, and Andrew Vowles formed Massive Attack, a group that immediately took the Bristol sound to a global audience.

In Massive Attack’s initial trajectory, Adrian Thaws aka Tricky made his bones as an artist on the first two albums, while a young producer and engineer named Geoff Barrow began his mentorship with producer Jonathan Sharp aka Jonny Dollar. While Geoff Barrow went on to form a groundbreaking band named after his hometown, Portishead, Tricky has become the quintessential exponent of the Bristol sound today.

Massive Attack – Unfinished Sympathy

Still regarded by many as one of the most important electronic records of all time, Unfinished Sympathy is an organic example of beat-sampling, soulful dance vocals, and high-brow string composition.

Starting with samples lifted from J.J. Johnson’s Parade Strut (Instrumental) and Planetary Citizen by John McLaughlin & Mahavishnu Orchestra, a drum loop inspired by Bob James’ Take Me to the Mardi Gras is then added, forming the main components of the groove.

In the studio, Massive Attack’s early creative approach was uncompromising and organic, with production techniques ranging from using sampled drum loops to classically orchestrated strings. Besides the group’s signature rapping in regional Bristolian accents, the vocals of Shara Nelson and Horace Andy became foundational to the Massive Attack sound.

There were always songs like Daydreaming that drew more directly from hip-hop roots. However, the songs that went on to define the group’s success were vocal collaborations with singer-songwriters like Tracey Thorn, Elizabeth Fraser, and Sarah Jay Hawley.

Massive Attack’s iconic debut, Blue Lines (1991) was recorded at Coach House Studios in Bristol, a location that would prove auspicious when Portishead recorded their groundbreaking and critically aclaimed debut album, Dummy (1994) in the very same studio.

Portishead began as a duo of Geoff Barrow and vocalist Beth Gibbons, with guitarist Adrian Utley joining shortly after their first album release. In the studio, Portishead developed a concentrated sound using a range of experimental tape and vinyl sampling techniques to achieve the gritty character for which the band became known.

Shortly after Portishead formed, yet another Bristol outfit began operating as remix producers. A duo comprised of James Lavelle and Tim Goldsworthy would steadily expand into the band known as UNKLE, another collective that would reach cult status as pioneers of what we call trip-hop today.

Portishead – Glory Box

With the ingenious sample use of Isaac Hayes’ Ike’s Rap II, Portishead immediately drew the attention of listeners in the US. Its homemade vinyl-sampled breakbeat with the soulful chromatic bassline underneath became the perfect foundation for the powerful lyrics.

Possibly the most unique aspect of the song’s arrangement is the way the emotional dynamics continue to rise throughout. The guitar elevates the choruses before the song erupts into a momentous industrial drum break, before slipping seamlessly back into the verse.

By the mid-90s, with electronic music beginning to spread its wings commercially, styles such as acid jazz and downtempo breakbeat were on the rise with pioneers like Kruder & Dorfmeister. Although the records in this DJ culture were largely instrumental, their popularity showed record labels they could take risks on new acts in this musical scope.

The Rise of Downtempo

The pioneering success of the Bristol scene changed the landscape in the UK. As a result, this completely transformed what was being played on the radio, and the type of acts that were being signed by major labels. However, even among this second wave of so-called “trip-hop bands”, there were artists who offered something fresh that reached outside of the US hip-hop adjacent template.

One of these acts began in Sheffield, a city well-known for being a melting pot for electronic bands who broke ground in synth pop and acid house throughout the 1980s. The band Moloko, formed when singer Roisin Murphy joined forces with producer Mark Brydon. Together, the duo created an eclectic sound that seemed to draw from Brydon’s experience working with Cabaret Voltaire.

Moloko – Fun For Me

Fun For Me represents a more acic house approach to trip-hop. By combining tough AKAI S1000 drum hits with a funky sawtooth bassline and some playfully ambiguous nonsense lyrics, an almost cartoonish atmosphere is created.

Throughout the track, interlocking percussive loops add texture and metric tension, allowing the genius of the vocal performance to come across like various characters in a psychedelic theatre production.

At this time, film soundtracks opened up another avenue for many artists. Trip-hop’s moody and occasionally quirky aesthetic featured in films like Hackers (1995), Stealing Beauty (1996), Batman & Robin (1997), and I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997).

All this momentum, combined with sales and chart attention in the US, allowed bands to bypass years of initial obscurity and stroll into pop success. One such explosion occurred only two years after the formation of the Hartlepool group, Sneaker Pimps, who were subsequently signed to Virgin Records and sold over a million copies with their debut album Becoming X.

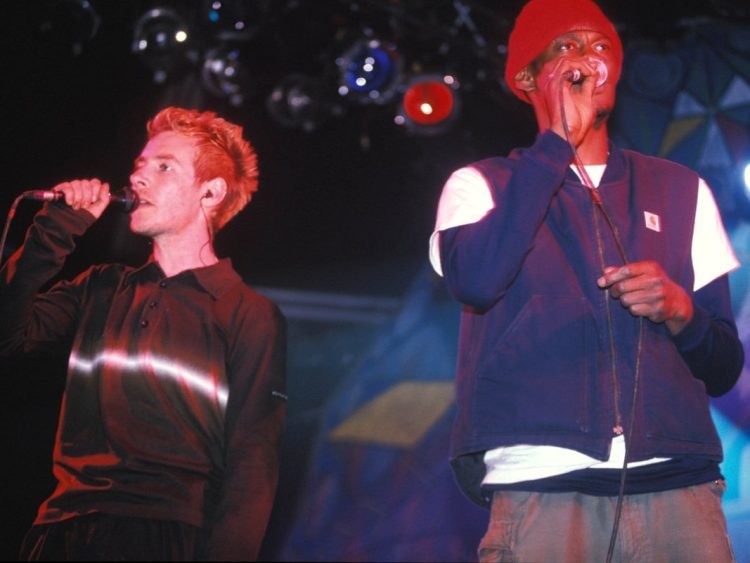

Sneaker Pimps – 6 Underground

Nellee Hooper’s edit of 6 Underground is the quintessential example of trip-hop in pop format. All the hallmarks are present like the hip-hop breakbeat and the mysterious harp melody sample from John Barry’s Goldfinger (1964) soundtrack.

The way the groove of the sub-bassline works off the rhythm section with the acoustic guitar chords is foundational. So, be sure you have your favourite headphones on, as the low-end doesn’t quite translate on laptop speakers.

From the mid-1990s onward, the influence of trip-hop and downtempo music reached its peak. As a result, major label acts began to show a dirgy beat-driven side of their sound on albums such as Depeche Mode’s Ultra (1997), Smashing Pumpkins’s Ava Adore (1998), and Madonna’s Ray Of Light (1998) where producer William Orbit drew from a more ambient sound.

1998 was also an important year in UK music, as we saw the monumental release of Massive Attack’s Mezzanine album and Morcheeba’s sophomore full-length release, Big Calm. Although commercial success brought trip-hop to a broader global audience, it was seen as a passing trend by many of the artists themselves.

Over time, Portishead’s Geoff Barrow became disillusioned with the success of the music he never intended to become a “dinner party” genre, as he states in this candid interview. He wasn’t alone in this sentiment, as Massive Attack founder Andrew Vowles left the band when the Mezzanine sound strayed too far from the original course. Meanwhile, after their first major tour, Sneaker Pimps parted ways with vocalist Kelli Ali for fear of playing into the cliche, and were promptly dropped by Virgin.

In the US, electronic music DJ and producer Moby was making inroads into the mainstream with his own style of sample-based downtempo electronica. Using every medium available at their disposal including advertisement placings, Moby’s management pushed Play (1999) to the widest global audience possible. This campaign was further solidified the following year, when the lead single Porcelain was featured in Danny Boyle’s film, The Beach. As a result, the album became the single greatest selling electronic album of all time.

Trip-hop Today

One of the most defining characteristics of downtempo music is the time it takes to truly appreciate it as a listener. This is one of the reasons, we believe, why the decline of physical album sales marked the end of more “album-orientated” genres like trip-hop within the pop music space.

Sevdaliza – Rhode

With the trip-hop scene long gone, artists like Sevdaliza can draw from its hallmarks like quotations from a long-lost epitaph. Although productions like this are DAW-based, they still manage to capture the gloomy, grinding industrial feel of the Portishead and Massive Attack records we love.

Instead of dusty 1980s samplers and synths, the digital sheen of the vocal effects and software instruments give the minimalistic production a futurist edge, while the bassline remains an homage to classic 90s tracks like Army Of Me and Fire On Babylon.

Like so many styles of music that existed before the dawn of digital music streaming, trip-hop developed its strong identity and connection with listeners from the physical sales of full-length albums. Without this, we can still draw inspiration from its musical ingenuity and punky spirit.

What’s more, the tempo of the average pop song today is slower, providing the perfect backdrop for creating new Trip-Hop-infused music styles. Could it be the next Robert Del Naja? All it takes is creativity.