One thing about Jimmy Cliff, he understood the assignment.

“My role was and is inspiring people,” he told me in 1999, backstage in Oracabessa, Jamaica during the filming of a television special honoring his longtime bredren Bob Marley. “To inspire people to want to live.”

Surrounded by TV cameras, several generations of the Marley family, and international stars like Lauryn Hill, Erykah Badu, Tracy Chapman, and Busta Rhymes, Jimmy Cliff did not waver, maintaining laser-like focus on his message and his mission.

“After a concert or after you listen to some of my music,” he explained, “I want to know that you feel empowered to get up and do something about your life and make your life better. And I think that’s what Bob was doing in his own way too. That’s the role that I’ve been playing, and that’s the role that I continue to play. I am a person who lives for this time. I don’t live in the past. And it’s just a great day today. I’m living now. I don’t know about tomorrow.”

Musician Jimmy Cliff attends the 25th Annual Rock And Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony at the Waldorf=Astoria on March 15, 2010 in New York City.

Stephen Lovekin/Getty Images

Living is what the iconic singer, songwriter, musician, actor, and humanitarian did best, even at age 81. And so his death on the morning of Monday, November 24 came as an utter shock to his family, friends, and music lovers around the world.

“To tell you the truth, we were not prepared for what happened,” his wife Latifa said yesterday, just hours after announcing her husband’s sudden passing following a seizure. “The day before, he was swimming and eating, very happy because we were ready to travel,” she said. “Everything was just perfect.”

Before jetting off to France for a family vacation, Cliff and his wife and their son Aken and daughter Lilty were planning to visit Jamaica for a few days to see how his beloved hometown of Somerton—a rural community near Montego Bay where he was born James Chambers on July 30, 1944—had fared during Hurricane Melissa.

“He wasn’t sick you know,” says trumpeter and vocalist Dwight Richards, who served as Cliff’s musical director for more than 20 years and ran his Sunpower Productions label and studio in Kingston. “This just happened overnight,” he says. “I spoke to him last week and we were planning to do some recordings. We were planning all kind of stuff. It’s just weird.”

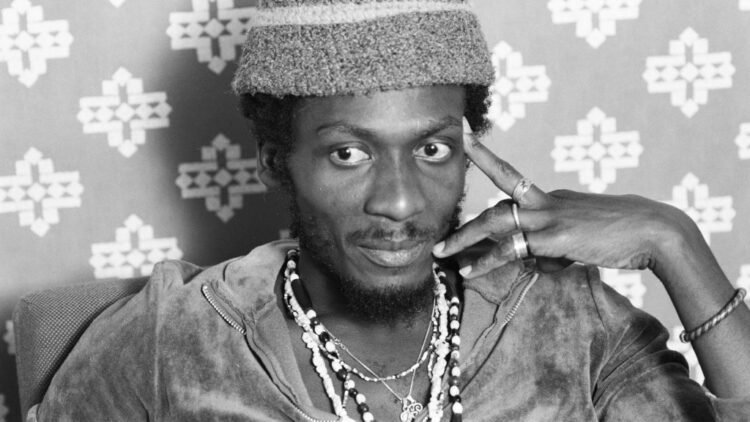

Reggae singer Jimmy Cliff at Island Records’ Studio One in London.

© Shepard Sherbell/CORBIS SABA/Corbis via Getty Images

The prevailing sense of disbelief is partly due to Cliff’s tireless creative longevity. To call him a “reggae legend” is to downplay the contributions of an artist whose voice rings out through every stage of modern Jamaican music.

“As a foundation man of the reggae I’ve always been one to go with the evolution of the music,” he told me for a 2004 VIBE article. “We evolved from ska to rock steady to reggae to rub a dub to raggamuffin and dancehall.” Jimmy Cliff seemed so unshakable, so constant, he became something like the Rock of Ages. “I am the living and the loving,” he sang in 1980, one year before Robert Nesta Marley flew away home to Zion. “I’m the shelter in a hail of thunder.”

“That man’s legacy is immense,” says Bounty Killer, who collaborated with Cliff on a remix of his song “Humanitarian” during the pandemic. “He transcends across like six generations and every continent. Jimmy was like a Cliff of inspiration to all of us Jamaicans. We definitely lost one of our greatest icons. And he was such a beautiful soul, the most humble human.”

Jimmy Cliff performs during the Mile High Music Festival at Dick’s Sporting Good’s Park on August 15, 2010 in Commerce City, Colorado.

Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

Buju Banton praised Jimmy Cliff’s “impeccable musical skills and a voice unmatched,” calling him “a true father and mentor who was there for me in times of need to remind me of my purpose with encouraging words and wise wisdom. He shall never be forgotten.”

Where other artists might consider kicking back in their late 70s, Cliff approached music like a lifelong vocation. “The past five years we kinda get really close to Jimmy,” says Roger Lewis, co-founder of the band Inner Circle, whose state-of-the-art Circle House studio in Miami—built with royalties from their Cops theme song “Bad Boys”—hosted many Jimmy Cliff sessions in recent times. Although Lewis says Jimmy couldn’t see too well, he points out that “sight no stop you from sing.”

When the day’s work was done, Jimmy would regale the Circle House gang with stories from his 60-year career. “Jimmy man, you need to write the book!” Roger would tell him. Now he wishes he had recorded some of those late-night reasoning sessions. “Bwoy the man pack up and gone Iya,” Lewis says mournfully.

Jimmy Cliff pendant l’enregistrement de la musique du film Club Paradise, le 1 aout 1986 à Londres.

Murray Close/Sygma/Sygma via Getty Images

The first fruits of those sessions appeared on Jimmy’s 2022 album, Refugees, released when the artist was 78. He described the title track as “not just a song, but a movement,” teaming up with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees to encourage listeners to volunteer, donate, and welcome asylum seekers into their communities.

Refuting negative attitudes towards them as the result of “ignorance and wrong judgement,” he said refugees that refugees are actually “quite extraordinary people, because they make miracles happen.” And he should know.

“Jimmy Cliff’s impact on world culture cannot be measured,” says filmmaker Reshma B, who interviewed the legend for her BBC documentary Studio 17: The Lost Reggae Tapes. “We had to set up really early because he had to get to the airport to go do a show somewhere,” she recalls.

Although waiting for artists to show up is part and parcel of being a reggae journalist, Cliff did not call at the last minute to say he was running late or cancel because he had to catch a flight. “He showed up on time, fresh dressed in this red snakeskin outfit,” Reshma recalls. “He was such a robust person and very energetic. He seemed pretty youthful for someone in his 70s.”

That snakeskin suit drove the audio man crazy—every time Jimmy moved, the material would creak. “We had to stop the interview at some points because the mic was picking up the sound of his suit,” Reshma says with a smile. “But he was very professional about that.”

Musician Jimmy Cliff attends the 6th Annual Focus For Change: Benefit Dinner And Concert at Roseland Ballroom on December 2, 2010 in New York City.

Neilson Barnard/Getty Images

Of course, Cliff had plenty of experience being filmed. “The idea of playing someone other than myself has always attracted me since school days,” said the star of the 1972 cult classic The Harder They Come, the first feature film to be written, cast, shot, and produced in Jamaica. “And I still think I’m a better actor than singer.”

The white Jamaican filmmaker Perry Henzel approached the original Starbwoy in 1970 at Kingston’s Dynamic Studios, just after recording the timeless classic “You Can Get It If You Really Want.” Magic was thick as ganja smoke in the atmosphere.

“A Caucasian bearded gentleman said to me, ‘I’m making a movie, do you think you could write the music for it?’” Cliff recalled. “What do you mean if I ‘think’?” the Starbwoy replied. “I can do anything!” Two months later he received a script with a note saying Henzel wanted Cliff to play the lead role of Ivan, a country boy who becomes “Rhygin”—a real-life gangster folk hero. Cliff seasoned the screenplay with his own experiences as an underpaid recording artist struggling to survive.

Jimmy Cliff, portrait in Rotterdam, Netherlands, 29th May 1986.

Rob Verhorst/Redferns

“The impact that ‘The Harder They Come’ had on Jamaica has never been seen before or after,” he told Reshma B, slapping his hands together to approximate how the movie, the music, and the rawness and realness of the actors hit international audiences. Where is the music coming from? they asked, lighting the fuse of a worldwide reggae explosion.

But Cliff was even prouder of the film’s impact on Jamaican audiences. “For the first time they saw themselves upon the big screen,” he said. “Never they saw themselves on the big screen before. They saw one of their own living the life. So it gave them a real identity beyond independence.”

The one-two knockout punch of The Harder They Come was the film’s soundtrack, packed with classics like the Melodians’ “Rivers of Babylon,” the Slickers’ “Johnny Too Bad,” Scotty’s early DJ cut “Draw Your Brakes” and the Maytals’ “Pressure Drop,” which showcased Toots Hibbert’s soulful roar.

Photo of Jimmy Cliff

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

But four breathtaking Jimmy Cliff songs, including the title track, the tune he recorded the day he was first approached about the film, plus “Many Rivers to Cross” and “Sitting in Limbo”—not to mention John Bryant’s badass cover illustration of Jimmy Cliff as Rhygin with a pistol in each hand—made this Jimmy’s landmark release.

“Very few single albums can be said to have changed music forever,” read the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ballot when Jimmy Cliff was nominated in 2010. Jimmy Cliff’s The Harder They Come is one. The album—and the movie that spawned it—introduced reggae to a worldwide audience and changed the image of the genre from a cruise ship soundtrack to music of inspiration and rebellion.”

One sheet movie poster advertises the Reggae crime film ‘The Harder They Come’ (New World Pictures), starring Jimmy Cliff, 1972.

John Kisch Archive/Getty Images

Mind you, this was four years before Damian Marley launched the first annual Welcome to Jamrock Reggae Cruise featuring superstars of reggae and dancehall.

Jimmy Cliff won, being inducted at New York’s Waldorf Astoria along with ABBA, Genesis, Iggy Pop & The Stooges, and the Hollies. “I wouldn’t be here without Jimmy Cliff,” said Wyclef Jean as he introduced the second reggae artist ever to join the Hall of Fame. The first, of course, was Bob Marley, inducted posthumously in 1994.

Jimmy and Bob shared much more in common than Hall of Fame membership. In 1962, when they were both teenagers, Jimmy brought Bob to producer Leslie Kong, who recorded his two first singles, “Judge Not” and “One Cup of Coffee.” As Bob himself recalled: “I was about sixteen, living in Trench Town. I always loved singing, I loved music, so over a period of time I wrote some songs.”

At the time Bob was working as a welder along with Desmond Dekker, who said Jimmy had given him a chance to record a record. “Jimmy was big then because he already had a hit,” Bob recalled. “I really love Jimmy because he always tries to help people out.”

Photo of Jimmy CLIFF

Bob King/Redferns

Being “big” and having a “hit” were strictly a matter of perspective. When he moved from the country to Kingston town, Jimmy settled in the Western Kingston ghetto known as Back-O-Wall, a humble shanty town that was later bulldozed to build the notorious Tivoli Gardens garrison. “Even though I wasn’t really and out-and-out rude boy, I was around them,” he said.

“Back-O-Wall was a place where everything kind of went on you know. There was Prince Emanuel, one of the Rastafarian elders. That was the spiritual part that went on in Back-O-Wall. And then there were a lot of people who were ‘bad men’ in whatever way. That’s where you would find them, and I hang out with a lot of them. You know, ‘Come here singer, come sing a song for we.’”

For the first song that he recorded, Jimmy was offered a shilling. “A shilling was maybe like a quarter,” he says. “I could buy a drink for that or maybe take a bus to school, cause I was still going to school then.”

Photo of Jimmy Cliff

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Jimmy told me he refused, adding with a laugh that “Then he threatened to beat me up.” But in retrospect, he still respects all the producers who created an internationally beloved genre from the ground up. “It wasn’t easy for them to do what they were doing… So I still have to sympathize with them in many ways.”

Jimmy was 17 when he met Leslie Kong, the youngest of three Chinese Jamaican brothers who ran an ice cream shop, restaurant, and record shop on Orange Street in downtown Kingston. His impromptu performance inspired Kong to start the Beverley’s record label, whose first release was a Jimmy Cliff 45 featuring “Hurricane Hattie,” a song about a category 5 storm that narrowly missed Jamaica, with “My Dearest Beverly” on the flip side.

He wasted no time pivoting to A&R, holding auditions for aspiring talents like Dekker and Marley who sang their ideas while he played the piano, judging which tunes would work for the label.

Reggae musician Jimmy Cliff performing in Kingston, Jamaica, 1977. During making of Harcourt Film ‘Roots Rock Reggae’.

Chris Morphet/Redferns

Two years later, Jimmy Cliff was chosen to join a delegation of Jamaica artists performing at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City along with Prince Buster, Millie Small, accompanied by Byron Lee & the Dragonaires. During the festivities at the Jamaica Pavilion he met Island Records founder Chris Blackwell, who signed him to the label and encouraged him to move to London, where he met rock stars like Pete Townsend and Joe Cocker.

On January 14, 1967 he shared a stage with the Jimi Hendrix Experience at the Beachcomber Club in Nottingham. Jimi and Jimmy struck up a conversation—“You can sing man… I just play my guitar”—and remained friends until Hendrix’s death the following year.

Jimmy Cliff performs live on stage at Paradiso in Amsterdam, Netherlands on November 11 2002

Frans Schellekens/Redferns

Rock stars love Jimmy Cliff. He never met Dylan, who reportedly called his 1970 record “Vietnam” the “greatest protest song ever written.” He did, however, speak with Paul Simon, who told Jimmy that he and Dylan sat up one night listening to his album Wonderful World Beautiful People.

John Lennon recorded a version of “Many Rivers To Cross”—as did Martha Reeves and Billy Preston, Joe Cocker, The Animals, Harry Nilson, Arthur Lee, Linda Rondstadt, Lenny Kravitz, UB40, and Cher—to name a few. Coldplay bassist Guy Berryman has admitted that the band’s touching “Fix You” owes “a bit of inspiration” to the song (those organ chords are unmistakeable).

Bruce Springsteen contributed a live version of Jimmy’s song “Trapped” to the charity album We Are The World and once invited him onstage to perform “The Harder They Come” together. Jimmy’s also collabed with Joe Strummer, the Eurythmics, Sting, and Kool & The Gang.

Jimmy Cliff performs during The Climate Rally Earth Day 2010 at the National Mall on April 25, 2010 in Washington, DC.

Kris Connor/Getty Images

Such cross-genre connections are not without complications. “We created this music out of a need for identity, recognition,” Jimmy Cliff told me. “Because before that, you know, to get any kind of respect we always have to play American music. And so we became frustrated with that… So you know, out of all those feelings, what we now know as reggae developed. It just came out. It’s got its place in the world, it’s got its place among all the forms of music. It’s there, and always will be there.” At the same time, Jimmy and other proud Jamaican artists recognized they couldn’t sell enough records in Jamaica to survive.

Latifa says her husband saw his music as a sort of fusion: “He used to always to say to me ‘Reggae Pop Rock,’ that is my thing.” He also participated in the International Song Festival in Brazil, shared the stage with Gilberto Gil, and released the track “Samba Reggae” in 1991, as well as touring African nations including a historic concert in Soweto in 1980—a decade before Nelson Mandela’s release from prison. The show is now considered a decisive moment in the fall of South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Until yesterday, Jimmy Cliff was the only living reggae musician to hold Jamaica’s highest official honor, the Order of Merit. In 1997 the University of the West Indies conferred upon him an honorary doctorate in Letters for his contributions to the culture. A seven-time Grammy nominee, he won Best Reggae Album honors in 1986 for Cliff Hanger and again in 2013 for Rebirth. But he wasn’t satisfied with merely winning—Jimmy wanted to win on TV.

“It’s a nice thing to be nominated for a Grammy,” he told CBS News. “However, I do think that people ought to see me on TV, accepting the Grammy. Not the way it is being done at the moment for a reggae Grammy where you just hear about it. It’s about time they show me on TV.”

1997: Jamaican reggae singer Jimmy Cliff (James Chambers)

BSR Agency/Gentle Look via Getty Images

In 2011, fresh off a performance on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy celebrated the release of his Sacred Fire EP by with an intimate acoustic set at a little spot on Houston Street called Miss Lily’s Variety. The guest list included author and free speech activist Salman Rushdie, actor Matthew Modine, Leon of Cool Runnings and Five Heartbeats fame—who is also a reggae singer—and painter-cum-film director Julian Schnabel.

I spun some tunes before Jimmy did his thing and reggae stalwart Pat McKay of SiriusXM conducted an irie Q&A. Standing three feet away from the 63-year-old living legend, perched on a barstool with his cap to the back and his eyes closed, strumming an acoustic guitar as he belted out “Many Rivers To Cross” was like an out-of-body experience. Getting a fist bump from Jimmy when I played his ska classic “Miss Jamaica” was an honor beyond words. When Jimmy was all done singing, he wiped a few tears from the corner of his eye. Classics are called classics for a reason.

“He always had a real passion for like the art he made and the work he made,” Jimmy’s daughter Lilty told me the day her father passed away. “So I think he would want to keep that alive in like other people. And to keep people passionate about the things that they care about, because he was always very outspoken about the stuff he cared about.

Jimmy Cliff performs at the Caribana festival in Geneva, Switzerland on June 10th, 2005.

Lionel FLUSIN/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

In one of his last conversations with his musical director Dwight Richards, Jimmy expressed his deep admiration for the Jamaican national hero Marcus Garvey. “Bwoy Dwight,” he said, “dem man deh was someone me look up to.” Dwight felt compelled to interrupt.

“But Dr. Cliff, you also is a great man,” he said. “I don’t haffi look pon Marcus Garvey to see my hero. You are my living hero. You are my living legend.” He explained that we don’t always have to look so far back to for people to emulate. Not when we have people right in front of us who paved the way. Jimmy laughed and replied, “Bwoy you’re right yunno Dwight! It’s good to feel that way.”

Since the news of Jimmy’s passing, Dwight’s phone has been blowing up. “Everybody callin’ me from all over the world,” he says. “And in Jamaica, all the radio stations spend lots of hours and hours. The prime minister, the opposition leader, everyone talks about Jimmy. Jimmy has songs that each of us can live,” Dwight adds. “Miss? We will miss him, but we will keep his music, his legacy, alive and well.” Dwight says “Moving On” was one of Jimmy’s favorite songs on the last album. The lyrics hit different today.

Jimmy Cliff performs live for fans at ASB Arena on March 27, 2015 in Tauranga, New Zealand.

Joel Ford/Getty Images